Researchers have been studying COVID-19 in homeless communities, specifically in shelters with two or more confirmed cases in the weeks prior to their study. They found that in these shelters with clusters of cases, the proportion of positive tests was higher than in shelters with lower amounts of previously reported cases. The results of this research were published in two Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) studies which included Karin Huster – a Global Health Clinical Instructor and graduate of the Masters of Public Health program, and Helen Chu, a Global Health Adjunct Assistant Professor – as authors.

According to the CDC, approximately 1.4 million people in America access emergency shelter or transitional housing each year. With these settings now posing huge risks for spreading COVID-19, public health teams performed investigations at these shelters, with the objective of testing all residents and staff.

One study, entitled Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 Infection Prevalence in Homeless Shelters, focused on clusters in Seattle, Boston, and San Francisco, while also testing a shelter in Atlanta with no previous cases. In the Seattle cluster, 17% of residents and 17% of staff members tested positive. Boston had 36% of residents and 30% of staff members test positive, with San Francisco finding 66% of residents and 16% of staff members to be infected.

However, in Seattle shelters where only one case had previously been identified, only 5% of residents and 1% of staff were infected. Numbers were also relatively low in the Atlanta shelter with zero previously identified cases, where 4% of residents and 2% of staff members tested positive. In total, 1,192 residents and 313 staff members were tested in 19 shelters across the four cities. Huster spoke about the things she and the team of authors learned from collecting this data.

“One of the key takeaways for us has been that implementation of proactive prevention measures in those congregate settings is key to prevent clusters from happening,” Huster said. “That means universal mask usage for residents and staff and adequate spacing of mats. Another key takeaway for us has been the importance of proactive testing of everyone in those congregate settings, regardless of symptoms, especially considering the significance of presymptomatic and asymptomatic transmission.”

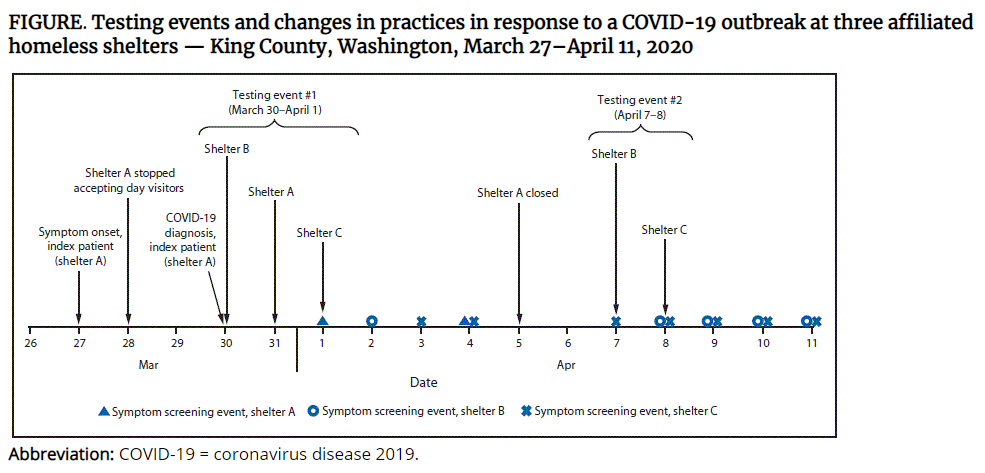

The second study, COVID-19 Outbreak Among Three Affiliated Homeless Service Sites, honed in on three shelters in King County. After Public Health – Seattle and King County was informed of an infected person at one shelter (Site A), they learned that residents from two other shelters (Sites B and C) had also used services at Site A. The study then offered immediate testing for all residents and staff at each shelter, finding that 19 of the 181 participants (10.5%) had COVID-19.

Repeat testing was offered to all residents and staff members who were not initially tested, or who tested negative during the first round. The second round revealed 18 positive tests among the 188 participants (15.3%), leading the team of researchers to provide recommendations to limit staff member rotations, encourage physical distancing, limit movement in and out of the shelter, train staff members on cleaning and disinfection, and move sleeping mats so that residents’ heads are more than six feet apart.

Both studies pointed out their own limitations as well. The study that covered multiple cities noted that testing represented only a single point in time, meaning it would not conduct repeat testing or account for future infections. They also did not screen residents or staff members for symptoms before testing them. Also, several residents and staff members from both studies declined to participate, or were not present at the time of testing.

Nevertheless, both studies found that the challenges inherent in homeless shelters created situations that can spread COVID-19. The reports noted that these shelters were often crowded and not conducive to safe distancing. Many homeless people also have pre-existing medical conditions or advanced age, making them more susceptible to contracting the virus.

“Homeless shelters, by virtue of their configuration and the realities of the population that live in them, are challenging environments to stop disease transmission,” Huster said. “Therefore, early, pro-active implementation of infection prevention control measures, and pro-active testing regardless of symptoms to quickly identify and isolate those who have been infected, is key.

As written in the King County study, doing so “potentially identified more infectious cases than symptomatic screening would have” and “prompt implementation of public health interventions to identify COVID-19 cases early can mitigate further transmission”, particularly among those in high risk communities.

“Well beyond the findings of this study, COVID-19 has demonstrated the urgency of resolving the homelessness issue and has forced us to address some of the most pressing needs of this population to prevent the spread of the virus,” Huster said.