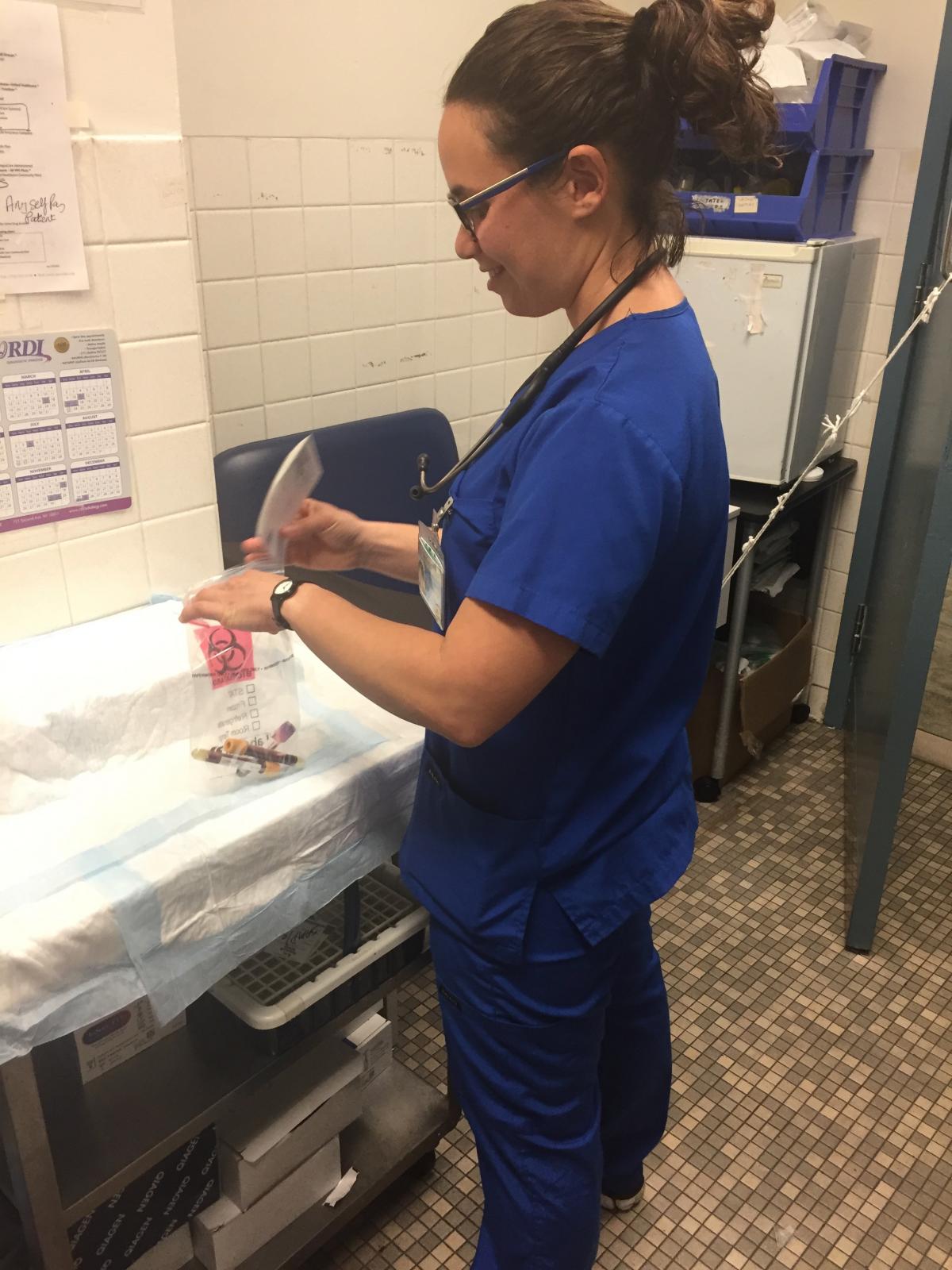

For Mariel Boyarsky (MPH, 2015), the global element of her Global Health background manifested itself when she became a registered nurse at Kings County Hospital in Brooklyn, New York in February 2019.

“It’s very international, a lot of my co-workers are from all over the world, and the patients as well,” Boyarsky said. “We see a lot of immigrant and first-generation patients from a wide variety of backgrounds. Many patients' illnesses begin in their home countries, then when their conditions worsen they end up in our hospital. Being on the clinical side now, I’m constantly thinking back to my public health training.”

That training came at the University of Washington, where Boyarsky studied from 2012-2015. Her hands-on experiences with members of the global health faculty stand out for Boyarsky as she reflects on her time in Seattle.

“I did my practicum in Uganda with Amy Hagopian (Professor, Global Health), looking at maternal and child health among rural coffee farmers in western Uganda. I worked with a Ugandan counterpart on a qualitative study on maternal and child health. That was a huge experience. I definitely used a lot of what I learned from Steve Gloyd’s (Professor, Global Health) class while I was there.”

During her time in the Department of Global Health, Boyarsky served as the conference coordinator for the 2014 Western Regional International Health Conference. Boyarsky and the 2014 conference committee chose "UNCENSORED: Gender, Sexuality, and Social Movements in Global Health" as the conference’s theme, at which she says “speakers and attendees grappled with some of the tensions inherent in these topics, and the conference provided an opportunity for the global health community to hear directly from individuals most impacted by the theme - from people living with HIV, transgender individuals, and activists living in the Global South.”

After graduating with a Master’s of Public Health, Boyarsky blazed a path toward nursing school, eventually landing at SUNY Downstate College of Nursing. But an important stop between UW and SUNY was crucial to her decision-making, Boyarsky says.

“Before I went to nursing school, I worked for the Washington State Department of Health in the refugee health program. That was part of what made me realize I wanted to be a nurse. That was a pretty quintessential global health role, and also very ‘Global is Local’ because we were doing global health in Washington.”

“One of the things we did was work with refugee community agencies as well as clinicians and public health officials, and using their guidance I created a survey that was administered one year after the refugees arrived to see how they were doing a year later. I believe the survey is still being used to inform how resources should be allocated, so I’m proud of that. I’m also really proud of the process. Instead of just sitting in my office I made a grassroots approach.”

That wealth of knowledge not only helped shape Boyarsky’s approaches to work, it also affected her thoughts about the intersectionality of health care. Today, working in a public hospital in America’s largest city, Boyarsky encounters several real life examples of this.

“Right now I’m in the ICU,” she began. “Recently I had a patient who was a gunshot victim, so I was thinking about violence and public health, intergenerational trauma, and a lot of different things that intersect with global health. I’m constantly thinking about the conditions and factors that led to my patient’s health status. There’s been so much more discourse around the discrepancies between white, black, and other races in terms of health outcomes. There are both really significant similarities and differences between what I studied and what’s happening here.”

Being in a nursing role and seeing the many branches of its tree gave Boyarsky an even greater appreciation for the University of Washington.

“Now that I know more about health care and have more experience, I realized how unique it was that social justice is part of the curriculum at UW,” Boyarsky said. “The faculty and students at UW – especially the people I’ve worked with – they really care about outcomes and process.”

When thinking about future classes and generations who will enter the Department of Global Health, Boyarsky encourages them to seek out as much information as possible, both within the department and outside its classrooms.

“My advice would be to talk to people who have careers in public health and connect over work you think is interesting. School is so engaging but it’s only two years, so think about what you want to do next. Take advantage of the fact that these world-renowned professors consider you a colleague.”